Germany’s top online news channel Der Spiegel published this article about my ADHD journey about my journey. And because so many of my non-German friends asked, here’s a full unedited AI-translation:

Germany’s top online news channel Der Spiegel published this article about my ADHD journey about my journey. And because so many of my non-German friends asked, here’s a full unedited AI-translation:

Entrepreneur with ADHD

“I don’t want to lose another company because I’m too scattered to write an email”

At 26, Randolf Jorberg became a millionaire by selling the tech portal gulli.com. He opened a bar in Cape Town, took on the mafia – and lost almost everything. What ADHD had to do with it.

By Verena Töpper – January 10, 2026, 09:53 a.m.

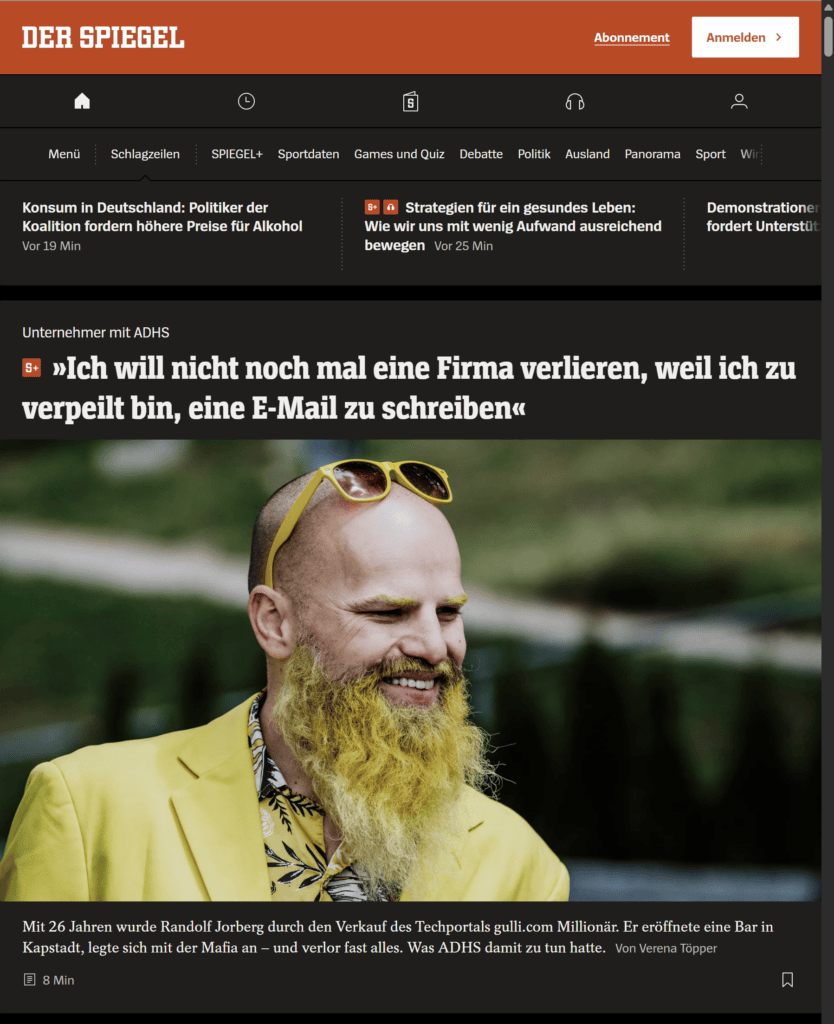

Randolf Jorberg, 44, doesn’t seem to hear the insult at all. “Look, a Minion!” a teenager shouts to his friend as they speed past him on an e-scooter at the harbor in Eckernförde. Jorberg doesn’t react – just as little as to the stare of an older man outside the café, who eyes his bright yellow beard with visible irritation and snorts.

He hardly notices the irritated looks anymore, Jorberg says. “What people see in the yellow says more about them than about me.” The yellow beard hairs are, for him, “a magnet and a spam filter”: “They attract the right people and keep the boring ones away. No one approaches me expecting average. If someone thought I was average – that would offend me.”

Jorberg the entrepreneur: being different as a business model

Randolf Jorberg does not want to please. He wants to sort. The yellow in his beard is a warning signal – and a promise. He builds business models that live off being different. That principle made him rich and took him to South Africa. But it also led him into problems that nearly broke him.

Jorberg’s yellow is the result of a long experiment. It started without color, without a stage, without an audience. In a small town on the Baltic Sea: Eckernförde. His mother still lives there; he is visiting. The local hardware store was the only place he was ever formally employed, as a temporary worker. Even as a student, he was looking for a way out of what he experienced as confinement – on the internet.

At 17, Jorberg founded gulli.com, a web portal for tech nerds whose forum quickly became one of the largest in Germany. With advertising revenue, he soon earned more than his teachers. In retrospect, he says, he feels sorry for them. “I got up in the middle of class to take phone calls. My attitude was: What do you even want to teach me? I already earn more than you.” In 2008, he sold gulli.com for a single-digit million euro sum, as he says. He was 26 at the time. To this day, he describes the sale as “epic.”

Jorberg likes to speak Denglish. “I’m good at disrupting,” he says when he means that he approaches things differently from others. That’s not a pose, he insists: “About 90 percent of my thoughts run in English.” As a student, he struggled with the language. His parents therefore sent him to a host family in the U.S. during summer vacations. That didn’t just help linguistically – with the host family, he used the internet for the first time.

Spotting a gap in the market: iPhones without mobile contracts

Seven months after selling gulli.com, Jorberg had two new ventures: the OMClub, famous for its annual big party of the online marketing industry, and the 3G Store, through which he sold iPhones without SIM locks. At the time, these were usually only available with a two-year contract from T-Mobile.

He never had a contract with Apple. “We bought the iPhones in Italy and sold them in Germany with a 30 percent markup,” Jorberg says. Back then, he didn’t think “there were limits to my abilities,” he says. “I was naturally high.” That’s how he steered into what he now calls “my first bankruptcy”: Soon, iPhones without contracts were available from practically every street vendor. The unique selling point was gone, revenue collapsed. For the sale of the domain and digital assets of the 3G Store, Jorberg still received 135,000 euros. His conclusion: “I can develop online models. But I’m not a merchant.”

“Catching up on life” in Cape Town

With “a lot of money in the bank and a lot of drive,” he arrived in Cape Town in 2007 and immediately fell in love with the city. Sun, sea, nightlife. “I had the feeling: Wow, here I can catch up on life,” he says.

Owning his own bar had been his dream since his youth. Now he had the money, the time, and the right place: Long Street in Cape Town. Jorberg bought a 700-square-meter house, had a tap system installed, and hired a designer. The designer chose yellow as the corporate color. Yellow like beer.

On August 2, 2013, Beerhouse opened. The children’s song “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall” became the motto: 99 beers, 24 of them on tap. “You can really say: from opening day on, there were lines out the door. It was a success from day one.” Eleven months later, he opened a second Beerhouse in Johannesburg.

Friends and acquaintances had warned him even before the first opening that, as a restaurateur in Cape Town, he would have to pay protection money. The mafia provided the bouncers and controlled the drug trade – that was how things were done in Cape Town’s nightlife. Jorberg wanted nothing to do with it. “I’m not willing to compromise there. For me, it was always clear: I am the only drug dealer in my bar – and my drug is alcohol.”

On surveillance footage broadcast nine years later on South African television, Jorberg can be seen brushing off a mafia intermediary. Together with other restaurateurs, he founded the “Long Street Association.” The idea: if no one pays, the mafia has no chance. It was a mistake.

> “In this case, I wish I had taken the warnings seriously.”

In June 2015, 18 months after the opening of the Beerhouse in Cape Town, one of the bouncers was stabbed to death. Jorberg describes it as a trauma. His decision had led to an employee losing his life. That was unacceptable. If he could travel back in time, he would have paid protection money from the beginning – or not opened the Beerhouse at all.

Ignoring warnings had paid off for him for a long time, Jorberg says. “People constantly told me: That won’t work, you can’t do that. I always proved that it did work. But in this case, I wish I had taken the warnings seriously.”

On the day of the attack, Jorberg wrote a letter to Helen Zille, then the governing premier of the Western Cape province. In it, he named the mafia boss he considered responsible. He says he wanted to publish the letter on his website. An acquaintance stopped him. “She said: If you do that, you’ll be dead next week.” Jorberg gave in. From then on, he paid protection money, collected donations for the family of the murdered bouncer, and organized a school scholarship for his daughter. “I see myself as a kind of godfather,” he says. “I feel responsible for the girl.”

Yellow fan Jorberg: from marketing gimmick to trademark

The summer of 2015 became a turning point. In July 2015, Jorberg traveled to Nairobi for the Global Entrepreneurship Summit, an international entrepreneurship conference. As a marketing gimmick, he put on a yellow suit – and was surprised at how many friendly conversations suddenly opened up. “Yellow immediately opens an emotional level,” he says. Smileys. Sun. Good vibes. Yellow simply puts him in a better mood, he says. Yellow T-shirts were followed by yellow socks, a yellow jacket. At some point, he reached for beard dye.

Evacuation flight back to Europe

Business was going well. He opened a third location in Pretoria. In retrospect, he says: “That’s when things started going wrong.” The Beerhouse in Pretoria burned money; “the place was oversized.” In Johannesburg, where he made the most profit, he forgot to renew the lease. When he realized it, the neighboring tenant had already taken over the space.

With a bank loan, he opened a new Beerhouse in a Cape Town shopping mall in November 2019. Four months later, South Africa imposed a particularly strict lockdown, and the hospitality industry came to a standstill. Jorberg returned to Europe on a flight organized by the German embassy – and from there launched a new attempt to deprive the mafia of business.

In a WhatsApp group that included politicians, journalists, police officers, and restaurateurs from Cape Town, he documented protection demands and named the masterminds. He then received death threats. Only in April 2023 did Jorberg dare to return – and handed over his records to the well-known South African investigative TV program “Carte Blanche.”

Gang boss Mark Lifman, whom Jorberg calls “evil personified,” sued him for the equivalent of 50,000 euros in damages for defamation. In November 2024, Lifman was supposed to stand trial as the alleged mastermind behind a murder. Shortly beforehand, he was shot dead. The lawsuit was dropped. “I’m still a bit disappointed,” Jorberg says. “I would have liked to see him in court.”

> “If I’m honest with myself, I have to say: I didn’t have it under control.”

By then, Beerhouse was already history. After the pandemic, Jorberg fell behind on debt repayments, and the house on Long Street was foreclosed.

“Instinctively, you always want to blame others for everything,” Jorberg says. The mafia. Covid. The bank. “But if I’m honest with myself, I have to say: I didn’t have it under control. I appear strong, but I have weaknesses. I’m easily distracted.” He could have prevented the foreclosure, he says, if he had just taken care of refinancing in time.

Success and scatter-brainedness, Jorberg says, had always gone hand in hand for him. “I have ADHD.” He received the diagnosis two and a half years ago. He describes it as a turning point, as “the answer to all the questions in my life.”

ADHD medication helped, Jorberg says, but is not a permanent solution for him. “It’s not like I take them and suddenly enjoy bookkeeping. They help, but I see them like crutches – and I don’t like crutches.” He likes himself the way he is. “I just don’t like my weaknesses. I don’t want to lose another company because I’m too scattered to write an email.”

Entrepreneur Jorberg: ADHD as explanation

He has founded a WhatsApp community for neurodiverse entrepreneurs: people with ADHD, dyslexia, or autism. With them, he feels understood, he says.

He has realized “that with my fight against crime, I was primarily fighting symptoms.” The real causes lay deeper – in lack of belonging, lack of perspective, lack of self-worth. “Many of the people who commit violence don’t primarily do it for money, but to belong.” He now sees his purpose in building platforms and spaces where people can connect, find belonging, meaning, and happiness.

Jorberg no longer believes in concepts of homeland, but in movement. In networks instead of places, in connections instead of securities.

He prefers to travel the world as a digital nomad. He doesn’t need much money for that: a hostel bed for ten dollars a night is enough, he says. He rents out his house in Cape Town for significantly more.

He envisions an online platform where neurodiverse people can network and coach each other. Whether it will become a viable project is still open. Only one thing is certain: Jorberg is returning to where it all began. He has secured a domain he once already owned: gulli.com.